Champa Sharath has been engaged in printmaking, a medium she has mastered with confidence in scale and technique. Her earlier show celebrated the hymns of the Hanuman Chalisa and invocations from Tulasi Das. This new set of works, “Avatars”, represents a departure from her preoccupation with women, allowing her to describe her visions in bold, graphic images that are striking avatars of women and their alter egos.

When women artists like Champa work with female representation, they often reject the traditional portrayal of the female body seen in...

Champa Sharath has been engaged in printmaking, a medium she has mastered with confidence in scale and technique. Her earlier show celebrated the hymns of the Hanuman Chalisa and invocations from Tulasi Das. This new set of works, “Avatars”, represents a departure from her preoccupation with women, allowing her to describe her visions in bold, graphic images that are striking avatars of women and their alter egos.

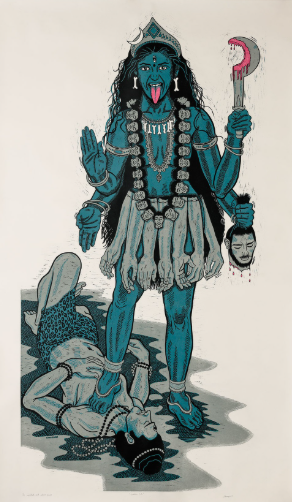

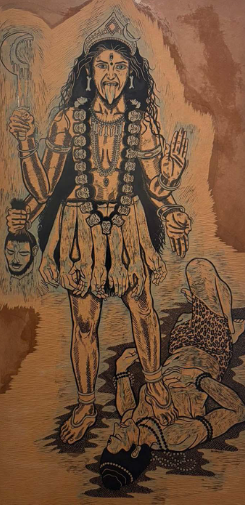

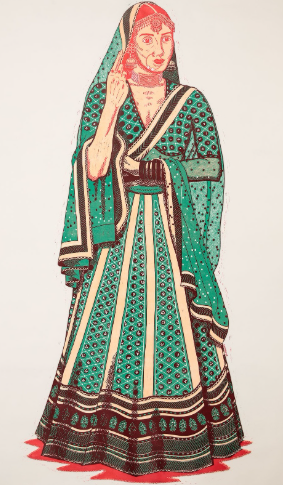

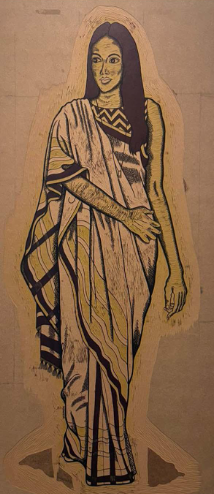

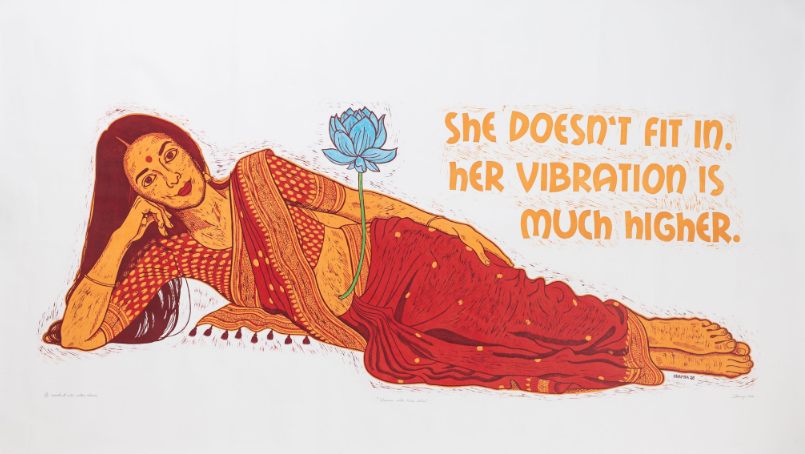

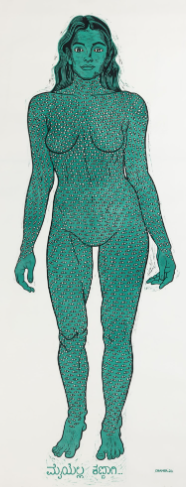

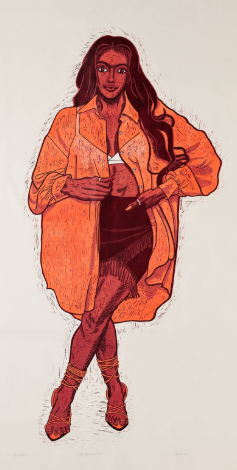

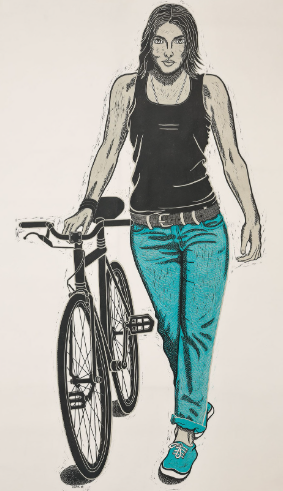

When women artists like Champa work with female representation, they often reject the traditional portrayal of the female body seen in art and mass culture. This type of imagery moves away from the idea of the body as a possession, a concept that John Berger argues is meant to appeal to a male viewer. This is evident in how little most female artists focus on presenting a “canonically beautiful” image. Instead, they concentrate on a new vocabulary of gestures and gazes to create a balanced relationship between the subjects. Champa has imagined the gallery space filled with overpowering women avatars, eight feet tall, dwarfing the viewer and engaging us in a visual confrontation and dialogue. Their stances are deliberate; they look you in the eye like epic characters from a projected film, or a cutout outside a film theatre. These representations of women are celebrated as icons with substance, their frontal performative stance enacting a character that the artist imagines, with her own iconography that draws from myth and lived reality, or is it her own self seen as a heroine playing many roles?

Her women are from her lived reality and mythology, which is so much a part of our cultural environment, like theatre; the artist slips in and out, from embodying the sacred goddess to the women next door. Their iconography varies from the saree-clad contemporary woman striding to complete her duties as a working woman to the nude, mythic female with eyes reflecting the male gaze. The mythological references of Kali vanquishing Shiva, female versions of Vishnu in Ananthashayana, Brahma, or Dattatreya with three heads and six hands, and a naga kanika are a few examples drawn from the archive of divinities that surround our physical and mental space. The characters represented are confident and stand in poses reminiscent of models on a runway, embodying an aesthetic that faces the camera or the audience. Sometimes her protagonists are seen engaging in simple pleasures, such as riding a bicycle, or confronting snakes fearlessly entwined around their bodies, or anxiously chatting about the pressures of the times, including FOMO —the fear of missing out.

Champa explores the potential of using the trope of shapeshifting by representing the other as oneself as an act of liberating the self, and being flexible to challenge herself and navigate different realms of consciousness. Her ability to adapt has enabled her to take on new challenges and navigate new circumstances.

Suresh Jayaram